The Graveyard as an Archive

December 1, 2019, Kolkata

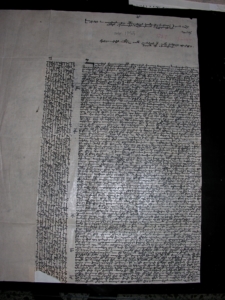

Letter of Tēr Harut‘iwn from Chinsura to All Savior’s Monastery in New Julfa, 10 January 1727. Source All Savior’s Cathedral Archive (ASCA) “Namakner Bangalayen,1712-1800”

On 10 January 1727, an Armenian priest stationed in the remote Dutch outpost of Chinsura (Chichra or Չիչրա in Julfa dialect and Chuchura in Bengali) named Ter Harut‘iwn wrote a lengthy missive to his superior in Julfa lamenting the melancholy decline of his parish’s erstwhile flourishing Armenian mercantile elite and the rapid rise of a new community 35 kilometers to the south. “Let it be known,” Ter Harut‘iwn wrote to primate David Vardapet, “there are only three well to do people [left] here who have money in their hands. The others are all bereft of any means.” Most, it seems, had accepted the invitation of Job Charnock who established an English East India Company outpost to the south of the Dutch in 1690. Of those who had remained, the wealthiest according to Ter Harut‘iwn was a middle-aged merchant and once a lowly “commenda” agent named Agha Nazar Hakob Jan who had arrived from Julfa in 1707 with hardly anything in his pocket save for a partnership contract with his wealthy capitalist master known as a coja (Khwāja in Persian Խոջա in Armenian) giving him a line of credit to trade with on his behalf for a measly portion of the profits. Nazar had managed his master’s money so parsimoniously that hardly seventeen years had passed from the time he first landed in India when he become one of the wealthiest Armenians in all of the subcontinent. As a token of what sociologist Pierre Bourdieu would later describe as “symbolic capital,” Nazar had done what all sensible merchants driven by a combination of piety and shrewd business acumen would do: he built a luxurious church on an Armenian burial ground in the newly established English outpost that would soon become the jewel in the British Crown and one of the greatest metropolises in the world. Nazar does not appear to have moved to this new metropolis himself, for all indications are that he lived the better part of his early days in India in the Dutch settlement to the north. So much so that he was considered a “local” there by the parish priest, whose letter has survived in the archives of the All Savior’s Cathedral in Julfa, Isfahan (see image below). “It is he who established the Calcutta Armenian church,” writes Ter Harut‘iwn, adding that the he had “spent seven thousand rupees on this church and built the edifice with his own money.” Had Chinsura not had an Armenian church as early as 1695, it is likely that Nazar would have built one there. The date of the establishment of his church, appropriately called the Holy Nazareth Armenian Church was 1724.

I visited this gleaming white edifice with its large compound crammed with hundreds of tombstones (my rough estimate based on the photographs I took is around 800 give or take a few dozen) with ornate inscriptions yesterday. It lies in the “Barabazar” district, an old marketplace between the northern indigenous “Black town” of Calcutta and the Southern “White Town” which served as the exclusive preserve of Protestant English residents whose East India Company had officially leased the three villages that became Calcutta from the Mughal authorities in 1698. Both then and later in 1717, an Armenian merchant residing in Chinsura Coja Israel di Sarhad had offered his diplomatic services as a “go-between” to pave way for the granting of a permit for the English Company to settle down there.

Barabazar where the Holy Nazareth Church was built was a “gray zone,” a liminal space, neither properly European nor indigenous or local. It was an important bazaar and a hub for merchants back then as it is today. As such, it attracted many an old trading community during the eighteenth century from the Armenians and the Portuguese, who were the first to be lured by Charnock, to the Greeks and Jews.

After a hearty breakfast, I decided to brave the long and uncertain walk from my hotel on the old Chowringhee Road to visit Nazareth’s church. My plan was to stop off first at the Portuguese Cathe

dral of the Holy Rosary (popularly known as the Murgihata Church), where I had dropped by the day before to photograph some Roman Catholic Armenian tombstones only to find a wedding ceremony unfolding inside the Cathedral. The walk took about forty minutes but involved many detours through narrow lanes and hidden alleys weaving through densely crowded bazaars. On the way, I stumbled onto the Beth El Synagogue built by Baghdadi Jews in 1856. The cacophonous medley of car horns, crows in the air, the occasional shrill cries of hawks, the crazy bustle of human life on the sidewalks (people cooking food, selling wares, sleeping on sidewalks or just walking by like me) was jarring on the senses. It made me think of Rimbaud’s famous line of the “total derangement of all the senses.”

dral of the Holy Rosary (popularly known as the Murgihata Church), where I had dropped by the day before to photograph some Roman Catholic Armenian tombstones only to find a wedding ceremony unfolding inside the Cathedral. The walk took about forty minutes but involved many detours through narrow lanes and hidden alleys weaving through densely crowded bazaars. On the way, I stumbled onto the Beth El Synagogue built by Baghdadi Jews in 1856. The cacophonous medley of car horns, crows in the air, the occasional shrill cries of hawks, the crazy bustle of human life on the sidewalks (people cooking food, selling wares, sleeping on sidewalks or just walking by like me) was jarring on the senses. It made me think of Rimbaud’s famous line of the “total derangement of all the senses.”

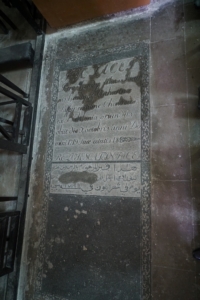

At the Murgihata church, I found a side entrance where a woman was washing the marble floor of the cathedral with a mop. I asked permission and entered hoping to spot two Armenian tombstones that had drawn me all the way here. I knew they were supposed to be inside the cathedral there but had never seen them. No one else I kn ow of has seen them either or recorded their inscriptions. One belonged to a monk from the Antonine order of Armenian Catholics in Mount Lebanon who was sent to these parts to collect alms and do missionary work in 1769. I read his letters this summer in an archive preserved in the mountains north of Beirut and took copious notes. Father Abraham Pirimian lived in Chinsura as did his brother Bartholomeus later on. From a 1915 study by the Jesuit scholar J.S. Hosten I had read before flying here, I learned that my monk was apparently called “Abraham de S. Lourenço.” According to Hosten, “In October 1770, March 1771, and February I779 his name appears in the Baptism and Marriage Registers of the Murghíhátá Cathedral. He died on September 20, 1782, and was buried within the (old) Murghíhátá Church.” I tried in vain looking for his marker as I did of the tombstone of Carapiet Mackertich Mooratian, the little-known brother of Samuel Mackertich Mooratian of Venice’s “Collegio Armeno” fame as well as that of the Mkhitarist father whose letters I have savored for many years with great excitement, Father Soukias Aghamalean. Both are said to have been laid side by side and inside the cathedral but their tombstones are reported to have vanished. After an hour of scanning the floors for Armenian script, there was no trace of them. I suspect they are beneath the new altar which must have been added in the mid-nineteenth century after multiple rounds of renovations on the earlier church, erected in 1700, renovated in 1720, transformed into a Cathedral that it is today in 1799 and further remodeled in the mid-1800s. My tombstones must have gotten lost or covered over in the shuffle. I suppose it’s a small miracle that I did succeed to find ten or eleven Armenian tombstones which I asked the cleaning lady wipe with her mop before photographing them.

ow of has seen them either or recorded their inscriptions. One belonged to a monk from the Antonine order of Armenian Catholics in Mount Lebanon who was sent to these parts to collect alms and do missionary work in 1769. I read his letters this summer in an archive preserved in the mountains north of Beirut and took copious notes. Father Abraham Pirimian lived in Chinsura as did his brother Bartholomeus later on. From a 1915 study by the Jesuit scholar J.S. Hosten I had read before flying here, I learned that my monk was apparently called “Abraham de S. Lourenço.” According to Hosten, “In October 1770, March 1771, and February I779 his name appears in the Baptism and Marriage Registers of the Murghíhátá Cathedral. He died on September 20, 1782, and was buried within the (old) Murghíhátá Church.” I tried in vain looking for his marker as I did of the tombstone of Carapiet Mackertich Mooratian, the little-known brother of Samuel Mackertich Mooratian of Venice’s “Collegio Armeno” fame as well as that of the Mkhitarist father whose letters I have savored for many years with great excitement, Father Soukias Aghamalean. Both are said to have been laid side by side and inside the cathedral but their tombstones are reported to have vanished. After an hour of scanning the floors for Armenian script, there was no trace of them. I suspect they are beneath the new altar which must have been added in the mid-nineteenth century after multiple rounds of renovations on the earlier church, erected in 1700, renovated in 1720, transformed into a Cathedral that it is today in 1799 and further remodeled in the mid-1800s. My tombstones must have gotten lost or covered over in the shuffle. I suppose it’s a small miracle that I did succeed to find ten or eleven Armenian tombstones which I asked the cleaning lady wipe with her mop before photographing them.

Four of the ten stones belong to one global family, the Shahrimanian/Sceriman, Xeriman family of Catholic Armenian diamond merchants from Julfa with a branch in Venice, another in Saint Petersburg, and a third in Chinsura. The Chinsura branch donated four tombstones to Murgihata’s smooth floor. The earliest Shahriman (Sarhat son of Manuel) was buried there in 1738. An uncle or relative followed him in 1755 (with his tombstone half covered by the altar) followed by two brothers Baghram and Zaccaria who died in 1763  and 1764 within half a year of each other in Chinsura and bequeathed their large fortune to the Mkhitarist congregation in Venice for the purpose of printing books in Classical Armenian.

and 1764 within half a year of each other in Chinsura and bequeathed their large fortune to the Mkhitarist congregation in Venice for the purpose of printing books in Classical Armenian.

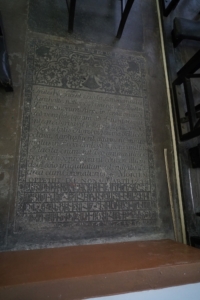

Phillipus Sheriman or Xerimanis 1755, tombstone probably too close to altar and covered halfway by new flooring.

In addition to a trilingual (Greek, Latin, and Classical Armenian) grave marker of an Armenian from Plovdiv (Philipopoli) named Georgius Johanni Drascoglu )ՅՕՎԱՆԻՍԻ ՈՐԴԻ ՋՕՌՋԻՆ ԴՐԱՍԿՕՂԼՈՒ ՖԻԼԻՊԵՑԻՕ who died in 1728 which I had seen before, the most unusual tombstone (image below) was that of a young man from Baghdad who died at the youthful age of eighteen. His name was “Petrus Hendy son of Joannes Hendy and Catharina Saffar, Chaldean by “nation” (what we would call Suryani or Assyrian today) and hailing from “Babilionia” (i.e., Baghdad). Boutros al Hindi as he was known to his kin breathed his last in Calcutta in 1719. His tombstone is in Latin and Arabic script. I find tombstone work in Calcutta (which I first began exploring on my first visit here in 2003) fascinating because tombstones are material culture’s way of reminding us that great hubs of trade like Calcutta in the “olden years” were always cosmopolitan hubs where people from different walks of life and a bewildering array of locations and cultures, like Drascoglu and Kendi, rubbed shoulders while alive and shared quiet pavements when dead.

An hour or so later, I walked over to the Armenian church. Its gleaming white steeple was barely visible behind a maze-like corridors and alleys congested by shops and stalls and thronging with people. A real beehive hopping with noisy activity. It took me several attempts and inquiries to find the entrance of the church. Before too long I walked into an oasis of quietude. It was like stepping inside an open air archive surrounded by trees. Isn’t this what cemeteries are after all for historians: archives where the dead speak in their silence? There was less cosmopolitan diversity in this cemetery that is for sure. Nearly all who were interred there were Armenian. However, lest one thinks that the great church that Agha Nazar Jacob Jan built in 1724 was a place of drab ethnic uniformity, consider the sheer diversity of “subethnicities,” a term anthropologists use to gauge regional differences within a larger ethic group. Sure, the vast majority of the deceased and certainly the movers and shakers with money all hailed from that shiny suburb on the hill known as Julfa, whose merchants once blazed their paths across oceans and over lands unknown. However, the courtyard of Holy Nazareth is also teeming with a variety of dead people from all imaginable Armenian subethnicities.

There are Armenians from: Yerevan, Gharabagh, Baghdad, Aleppo, Tiflis, Madras, Batavia (Indonesia) and wherever else the global Armenian diaspora stretched itself. Accompanied by one of the Bengali ground keepers and later by Boghos Stepanian a local gentleman whose mother is a Bengali and father an Armenian from Baghdad (I think) and who speaks fluent eastern Armenian since he graduated from the Armenian college, I spent a good two hours photographing the tombs of all, great and small, counterclockwise from the entrance of the building that Nazar had built. Nazar appears to have moved to Madras in the 1730s and died there around 1744, leaving an enormous fortune to his nephew Shahamir Shahamirian, including a mansion that later became “Lord” Clive’s residence and the Governor’s mansion in Madras’s “White Town” where Armenians were not allowed to live.

There are Armenians from: Yerevan, Gharabagh, Baghdad, Aleppo, Tiflis, Madras, Batavia (Indonesia) and wherever else the global Armenian diaspora stretched itself. Accompanied by one of the Bengali ground keepers and later by Boghos Stepanian a local gentleman whose mother is a Bengali and father an Armenian from Baghdad (I think) and who speaks fluent eastern Armenian since he graduated from the Armenian college, I spent a good two hours photographing the tombs of all, great and small, counterclockwise from the entrance of the building that Nazar had built. Nazar appears to have moved to Madras in the 1730s and died there around 1744, leaving an enormous fortune to his nephew Shahamir Shahamirian, including a mansion that later became “Lord” Clive’s residence and the Governor’s mansion in Madras’s “White Town” where Armenians were not allowed to live.