A Lock of Hair

May 10, 2015

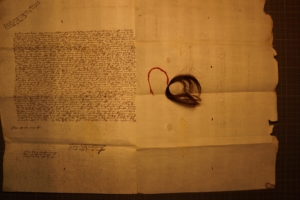

Letter No. 1534 in the Santa Catharina collection is unique among the other letters because it has a lock of a woman’s hair, tied to a fine red ribbon, remarkably preserved in its eighteenth-century “envelope.” I discovered it in 2003, nearly three-hundred years after it was first posted. It was part of collection of more than two thousand family and mercantile letters traveling on an Armenian-freighted ship the Santa Catharina. I remember being stunned by this woman’s hair still pressed inside the long epistle written on a rice-paper-like surface. Was this silent witness from the past waiting for all this time inside a box at the Public Record Office in Kew for me to discover it? I was a graduate student (and not sufficiently trained) after all working on the intellectual and cultural history of this woman’s son at the time of my discovery, so imagine my shock when I began to read the letter and discovered who its author was!

The author of the letter is an Armenian woman in New Julfa/Isfahan who identifies herself as “Annam, the maid of Christ.” Her identity has come down to us through historical sources on New Julfa mercantile history largely because she was the matriarch of a famous Armenian family residing in India. Her name was Anna Khatoon, the wife of a wealthy Armenian textile merchant residing in Madras and Pondicherry known as Khwaja Sultan David or Sult’anum ordi Davutkhani. Indeed, Annam’s letter with her hair is addressed to her husband “in Madras or wherever he may be.” Letter No. 1534 is also unique because Sultan David, the letter’s addressee, was the father of perhaps the most important Armenian of the eighteenth century, Agha Shahamir Sultanoom, arguably among Madras’s richest businessmen and a leading intellectual figure among the Armenian elite of the eighteenth century.

One of the two books I am working on at the moment, “The Final Voyage of the Santa Catharina,” will be a global microhistory of the Indian Ocean based on the ship’s traveling archive, a tiny seaborne geniza. Each chapter will have a title based on the paper cargo of the ship, and so naturally my most exciting chapter will be entitled “A Lock of Hair” and will use this nearly impenetrable letter as a point of departure to retell the life history of one of the most fascinating Julfan families of the early modern period, the Shahamirians descended from Sultan David. My chapter will use this letter and about a dozen other pieces of correspondence addressed to either Sultan David or his more famous son, Shahamir Shahamirian, to rewrite the history of Armenian and Indian Ocean constitutional thinking, a topic that has hardly received the scholarly attention it deserves despite the first steps taken by the brilliant and late Christopher Bayly. More precisely, Anna Khatun’s lock of chestnut-colored hair will serve as a focal point of entry into how her son and grandson (Shahamir Agha and Hakobjan, respectively) wrote a proto-constitutional, republican treatise in Madras in 1787 for a future republic of Armenia about a hundred and thirty years before such a state would even find its way onto a modern map.

Interestingly, Sultan David’s tombstone (of interest all by itself) was discovered about fifteen years ago near Vietnam at the bottom of the South China Seas. It was inside the wreck of an East Indiaman, the Earl Temple, that “struck the reef” and sank sometime in the early 1760s while the vessel was on its way to Manila to be refitted before calling at Canton. According to Susan Schoppe, who identified the ship, Sultan David’s gravestone, measuring 210 cm in height, 104 cm in width, 24 cm in thickness, and weighing a whopping 1135 kgs, was found among other detritus of a ship that had sunk to the ocean floor. It was a midst a debris field that included musket shot, cannons, anchors, iron ingots, several shoe buckles, eating utensils, spigots, decanter stoppers as well as a stone pillar from a Hindu Temple and two other tombstones. Apparently, Sultan David’s last marker in this world (see image below) was used as ballast for the English East India Company ship at the time of the British conquest and looting of Pondicherry in 1761.

Sultan himself was a textile merchant residing in Madras when he was forcibly taken and resettled in the French trading center after the French conquered and looted his home town in 1748. He died in the French colonial outpost in 1754 and until the remains of the “Earl Temple” were discovered, no one seemed to have known where and where Sultanum had breathed his last. With this lock of hair letter, we are now uniquely positioned to shed light on a whole other dimension of Sultan’s family history and how he and his son Shahamir became among the wealthiest members of Madras’s high society. Incidentally, Sultan to whom letter 1534 is addressed did not receive this message nor could he take a whiff of his wife’s lock of hair to know that she was indeed the one writing him the letter. The British navy intercepted the ship on which Anna Khatun’s letter was traveling and sent it, along with the other paper cargo of the ship, to London to be used as exhibits for a high-stakes trial, after which the letter ended up in the archive never to be seen again until I stumbled upon it twelve years ago.

Governor’s mansion and residence of “Lord” Clive in Madras/Chennai, formerly the house of Sultan David

I have been puzzled for twelve years now as to why Anna Khatun felt compelled to enclose a lock of her chestnut-colored hair in her missive. My only hunch as to why she would insert it and ask her husband to smell it, is that she used an intimate body part (hair was very personal and symbolic in the Middle East as elsewhere then as now) as an olfactory signature. Since she was probably illiterate (she had someone else possibly a priest write her letter) and did not seem to own her own seal, she wanted her husband to know that it was she who was the author of the letter. Sultan David was after all a wanted man in the Iran of Nadir Shah, the Afsharid tyrant having issued an arrest warrant for him and had requested the English East India authorities “to get him Seized with all the Estate and dispatched to Ispahan, that he may come & Satisfie the Petitioner [Coja Nazar’s second sister Tamar, who appears to have been evil character based on the sources] in her Demand, retire to his own Country and Behave as one of the Inhabitants there.” One reason for this was that Sultan had inherited on behalf of his wife Annam the huge fortune of Coja Nazar Jacobjan, Annam’s billionaire brother and Sultan’s commenda master, who owned the several houses in the “White Town” of Madras, one of which became Lord Clive’s residence after it was confiscated by the British officials from the Shahamirian family.

Է

Ամենայ պայծառ սահապ դոլվաթ սահապ աղայ սուլթանումին

՚ի քրիստոսի աղախին անամէս. Արզ բանդայգի հասցէ վերոյ ,,,,ղուլուղումն որ խնդրեմ բարերարէն որ ս[ա]հ[ա]բիս հերկար ումպրօվ պայծառ եւ միշտ բարի աջողռւթեամբ պահեսցէ մինչի խորին ծերութիւն պարի. ղսմաթ [قسمة qismat, Division, distribution; partition of inheritance; lot, share; fate, destiny, decree of God; fortune] էսպէս ելաւ որ աստուծոյ ողորմութիւնն խասաւ ժ [10] տարէն յետ աստուած հրամանոց բ [2] տղայայ տվէլ ինշալայ մինչի արզիս տեղ խասնելն. ումիտ աստուած որ գ [3] գնի դառցէլ։ օրհնեալ է աստուած որ կենդանի մնացինք խիզանով մինչի կէտս. աստուած լայեղ [لیق laiq (v.n.), being proper (action), fitting well] ետես. որ հրամանոց աչկաց լուսէնք գրեցինք. էս գ [3] տղին մինն պարոն շահմիրնայ որ ղուլուղ արեկ. բ [2] քն պարոն շահմրին տղէքն աստուծով լէվ խաթիր բերես որ ա[ստուծո]յ ողորմութիւն խասաւ որ շահմիրն էս քաղքէն դուս արեկ

To the most illustrious wealthy master Agha Sultanum,

From the maid of Christ, Annam, let it be submitted in the service of the above mentioned [i.e., Sultanum son of Davutkhan] that I beseech the Benefactor that he keep my master luminous and always with good success in a long life until his ripe old age. Our fortune was such that the compassion of God has felll upon us, and after ten years, God has granted your lordship two boys. With God’s will [inshallah] until my note reaches there, I hope to God that it [the number of boys] shall reach three. May God be blessed that we have remained alive with the [whole] family until this point. God saw it suitable for us to write to congratulate you. Of these three boys one is Mister Shahmir […] and the two others are the sons of Paron Shahmir […]

Last page:

[top left margin] հակոբ վարդապէտս սահաբիս շատ բարօվ կառի. ասմայ եսէլ ուրն հատուկ գիր կը գրեմ

Ալիղուլի խաննէլ թագավորեն դրէլ. նազարին տվին. աստուծոյ ղզար բերան փառք. Մին լէվ սհաթէր. ինշալայ աստուծոյ ողորմութիւնն խասնի. բարօվ հրամանքտ գոս. ոտնօվ դէմ գոյ ծամլկիցն կտրէլամ դրէլ գրումս. խոտ կաս մինջի բարօվ գոս յերէսն պած՚ճես. էլ հէնց ահվալ խէր լիցի սահաբիս յերկար ումպր եւ միշտ պայծառութիւն

ղամար իդ թիւնն փոքր աճլբ

սահապիս հնազանդախոնար ծառայ ակոբջան դի շահմիր. թասլիմ բանդայգի հասցէ

ի խոնարագունեղ փոքր ծառայից ծառայ յարութիւն մարտիրոսէն

թասլիմ բանդագի հասգէ

Jacob the archimandrite [vardapet] sends many greetings and says I too will write him a separate letter.

They have placed Ali Quli Khan as king… A thousand thanks to God for it was a good time [for us all]. Let God be willing that his compassion falls upon us and that your lordship comes [here] safely and stands before [me]. I have cut a lock of my hair [literally the extremities of my hair from Classical Armenian Ծամ] so that you may take a whiff of it (խոտ<հոտ) until you retiurn in safety and kiss [my] face. And may my master have a long life and always be illustrious.

[Written on] 24 of Ghamar, in the small calendar 132, (August 9, 1747)

My master’s most obedient servant, Hakobjan son of Shahmir, salutations.

From the most menial small servant of servants, Harutiwn di Martiros, greetings.