Absalom, Absalom!

July 17, 2018

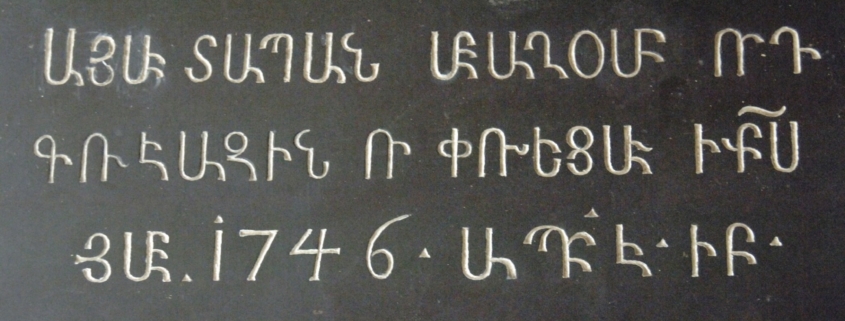

His tombstone with its strangely twisted Armenian letters (as if by some miracle a few of them have sprouted extra limbs like the Indian goddess Lakshmi) lies stretched across the floor inside the vestibule of the Սուրբ Խաչ or the Santa Croce degli Armeni church here in Venice. Three short lines in capital letters and only twelve words carved onto a black marble surface with white uncial lettering. At first site, they look deceptively easy to read. Not so, I found out several years ago. The Lakshmi-effect: or one simple letter in majuscule Armenian script transfigured by the addition of one or two extra lines (let’s call them goddess’s fourth or fifth hands) can save space when carving on a hard and expensive surface like marble; by producing two or three sounds instead of the usual one, it may save money and requires less carving while simultaneously causing great confusion and stress to the untrained eye. Known as Կապգրութիւն or Կցգրութիւն (Kapgrut‘iwn or kts‘gruti‘iwn) or connected or conjoined writing, this practice was fairly popular in Armenian writing until the eighteenth or early nineteenth centuries. It has been studied by many Armenian paleographers but none perhaps as well as A. Abrahamyan in his influential paleography manual (Հայոց գիր եւ գրչություն). I used this work to good effect as a textbook earlier this year when I taught my early modern Armenian paleography seminar at UCLA.

The merchant whose name is written in the style of an Indian dancing goddess died alone in his room in a house he rented in the Parrocchia di San Severo in Venice on 22 April in 1746. His neighborhood or parish is in the Castello district, where I am renting an apartment this summer. He was about eighty-one years old when he died according to the sacristan or custodian of the Chiesa Parochiale di S. Severo, one of three he worshiped in and to which he bequeathed money.* His name was Կուլիազ որդի Ապիսողոմի (aka Guliaz di Apsalon or “Giulias de Ipsalon Armeno”). Unlike many of Venice’s high-rolling Armenians, he did not hail from the sprawling township of New Julfa near Isfahan. He came from the backwaters of Empire, a town known as Shorot (Շորոթ) that nonetheless produced many a globetrotting Armenian merchant or priest in search of a better life or more fortune in places like Venice or Transylvania. (Sookias Aghamalian, the Mkhitarist monk who died in Calcutta, and Samuel Mooratian of Madras are the two well known Shorotsis with Venice and Transylvania connections that come to mind) My merchant’s tombstone is sparse when it comes to details. It reads more like a coroner’s report and consists of twenty-eight separate letters of which a full eight have extra limbs.

The merchant whose name is written in the style of an Indian dancing goddess died alone in his room in a house he rented in the Parrocchia di San Severo in Venice on 22 April in 1746. His neighborhood or parish is in the Castello district, where I am renting an apartment this summer. He was about eighty-one years old when he died according to the sacristan or custodian of the Chiesa Parochiale di S. Severo, one of three he worshiped in and to which he bequeathed money.* His name was Կուլիազ որդի Ապիսողոմի (aka Guliaz di Apsalon or “Giulias de Ipsalon Armeno”). Unlike many of Venice’s high-rolling Armenians, he did not hail from the sprawling township of New Julfa near Isfahan. He came from the backwaters of Empire, a town known as Shorot (Շորոթ) that nonetheless produced many a globetrotting Armenian merchant or priest in search of a better life or more fortune in places like Venice or Transylvania. (Sookias Aghamalian, the Mkhitarist monk who died in Calcutta, and Samuel Mooratian of Madras are the two well known Shorotsis with Venice and Transylvania connections that come to mind) My merchant’s tombstone is sparse when it comes to details. It reads more like a coroner’s report and consists of twenty-eight separate letters of which a full eight have extra limbs.

ԱՅՍ Է ՏԱՊԱՆ ԱԲԻՍԱՂՈՄԻ ՈՐԴԻ ԳՈՒԼԻԱԶԻՆ ՈՐ ՓՈԽԵՑԱՒ Ի ՔՐԻՍՏՈՍ ՅԱՄԻ 1746 ԱՊՐԻԼԻ ԻԲ [22]

THIS IS THE TOMB OF GULIAZ SON OF ABISAGHOM [<Hebr. Abǝšālom] WHO PASSED ON IN THE YEAR 1746 ON APRIL 22.

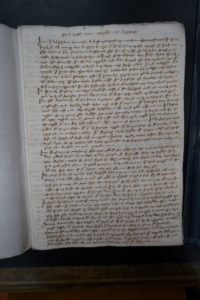

Far more revealing of the man and unknown to me till yesterday is the actual will that the son of Absalom had arranged to be written a year before he died. Since he was already too old and infirm to even hold a pen or quill by himself he dictated his thoughts to Santa Croce’s parish priest, Dionysus Manase (Դիոնէսիոս Մանասէ վարդապէտ) from Istanbul. I found and photographed this will yesterday thanks to a footnote in Giorgio Nubar Gianighian’s work** Stored as “Testamento di Giulias, figlio di Absalon, 1745,” in ASV, “Cancelleria Inferiore,” busta 70, no. 413, the will has important information on the sort of man the testator was and the kinds of ties (both with family and associates) he kept. The son of Absalom had a mother named Zarif (Զարիֆ) and a brother, Petros (Պետրոս). His business partner or patron (it is unclear from the will) was Yohannes son of Piri from today’s Yerevan suburb of Kanaker (քանակեռցի Փիրի որդի յօհանես). Like many of his compatriots in Venice, he was deeply pious and a fervent catholic. He left the bulk of his fortune to three churches that defined the arc of his life in the Adriatic city: the parish church of San Severo, demolished in 1829 to make way for a prison, the Armenian church of Santa Croce where his funeral took place and where was interred, and the church of Abbot Mkhitar on the island of San Lazzaro. He went to great lengths to specify the kinds of candles to be lit when mass was said for his soul every year and specified where he wished his coffin to be placed during the funeral and how it had to be covered by a black cloth. This religious ethos was reflected in the books he owned, which were few but whose value was not insignificant. He lists three of them in will: the Abridged Theology of the Blessed Albert the Great, published by Abbot Mkhitar in 1715, the Commentaries on the Gospels by the great Jesuit father and Armenologist Jacques Villotte, and the three-volume Book of Confessions by the equally esteemed proselytizer and Armenologist, Clemente Galano. These he gifted to father Dionysus Manase.**** The will’s original Armenian begins with the following lines in Grabar:

Է

Է

Թիւն փրկչին 1745. Սեպտէմբերի. 27։ ՚ի վենետիկ։

Ես ՚ի նախիշիվանու գաւառէն. եւ ՚ի գիւղաքաղաքէն շուռութու, Աբիսողոմի որդի Կիւլեազս գոլով ըստ ամ[ենայն]ի առողջ մտօք եւ զգայ[ութեամ]բ, զայս իմ կտակ յօժար սրտիւ արարի, զի կտակս այս զկնի մահուան իմոյ հաստատուն եւ կենդանի լիցի. եւ վ[ա]ս[ն] այս[ո]րիկ զայս[ո]սիկ երկու բարեպաշտ անձինս վաքիլ արարի. որ է իտալիավար քօմմիսարիօ Թեսթամենթարիօ [commissario testamentario], որոց մինն է Մղտեսի Աբելի որդի պարոն Առաքելն. եւ միւսն է ողորմած հոգի մանուկի որդի պարոն թէոդորոսն. որք իմ թեմիսուկներով առնելիքնիս առնուն.…

In the Name of God

In the year of the Saviour 1745, September 27 in Venice

I Absalom’s son Guliaz, hailing from the province of Nakhjevan [Nakhishivan, as it is spelled] and the town of Shorot [Shurut], being of sound mind and healthy body, of my own free will established this as my last will and testament following my decease. On account of this, I nominate two pious individuals as my representatives [Vakil/Wakil], which in the Italian language is called K‘ommisario testamentario [commissario testamentario], of whom one is Paron Arakel the son of Mghdetsi Abel and the other Paron Teodoros the son of the deceased Paron Manuk, so that the latter shall receive what is due to me with my bills (temesuk)…”

Below are a few photos of the material remains of the son of Absolom who has occupied my thoughts lately. The first in the gallery is the tombstone followed by the Armenian will, a register book on his inheritance money from the Santa Croce archives, and photo of me with Giorgio Nubar Gianighian with whom I had the pleasure of talking about the Absolom and his rented house over a pizza with my friend Minas who made the meeting possible. Lastly, there is a photo of the place where the son of Absalom’s parish church apparently was before its demolition and probably the street where he rented a house.

* See the extract from the “Libro de Morti” in “Procuratia Eccelentiss[ima] di Citra, e Chiesa di Santa Croce degl’ Armeni,” (Stampa booklet), 36 in ASV Procuratori di San Marco Busta 180 (Santa Croce),12. This church is no longer around since it was

** Guliaz di Absalom seems to have been the only resident merchant from Shorot at the time of his death. The wealthiest merchants with the most clout in Venice were from New Julfa, though the numerical majority were from Gapan in today’s southeastern part of Armenian republic. For instance, a ledger book for the Santa Croce church provides the following tantalizing information on the tiny community in this Adriatic city. According to the latter, on March 12, 1149 (1701) 44 merchants went to Church to deliberate and vote. Of these 44, the first 16 are listed separately as Julfans and another 18 are listed also separately as hailing from Ghapan. The remaining 10 are from other places («Եւ Այլք») in the global Armenian diaspora. This means that, though probably the wealthiest element in the community and clearly numerous, the Julfans were not the majority. If anything, the Ghapantsi merchants seem to have dominated. All the names of these merchants are registered in this ledger book.

*** Giorgio Nubar Gianighian, “Segni di Una Presenza,” in Gli Armeni e Venezia, dagli Sceriman a Mechitar: Un momento culminante di una consuetudine millenaria (Venice: Istituto Veneto di Scienze, Lettere ed arti, 2004), 59-92.

*** Giorgio Nubar Gianighian, “Segni di Una Presenza,” in Gli Armeni e Venezia, dagli Sceriman a Mechitar: Un momento culminante di una consuetudine millenaria (Venice: Istituto Veneto di Scienze, Lettere ed arti, 2004), 59-92.

**** Եւ իմ գրեանքն, որք են ալպէրթն, Վիլօթի ավետարանի մեկնիչն. Դաւանութեան գիրքն. կղեմեսի երեք հատորն, տրեսցեն ՚ի յիշատակ իմ կոստտանդնուպօլսեցի դիոնէսիոս Մանասէ վարդապետին…