Of Hats and Men: Notes on Sartorial Practices and Collective Self-Fashioning in the Early Modern Armenian Diaspora

February 3, 2013

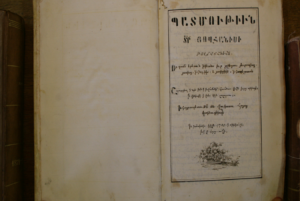

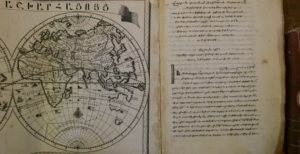

In the late spring of 1768, the British East Indiaman, the Earl of Egmont, began taking on water in the Indian Ocean only a few months after it had left the port of Madras on its way to London. After some deliberation, the captain of the Egmont decided to make a forced emergency stop at the French colonial outpost on the island of Mauritius. On board the ship was an Armenian gem merchant, Ter Hovhannes Tovmachanian, from Istanbul/Constantinople who later became a Catholic Armenian monk in Venice and wrote a lengthy autobiographical account of his travels across thirty countries where he recounted his experiences in Mauritius. On folio 273 of his manuscript (now preserved in the manuscript holdings on the island of San Lazzaro), Tovmachanian describes his strange encounter on the island with its French Governor-General who astonished Tovmachanian by greeting him in the peculiar mercantile dialect spoken exclusively by Armenian merchants from New Julfa:

Եւ Թովմաճանն զգեցեալ էր զպատուական Մատրասի պարոնացն զգեստն, եւ զգտակն նոցին մանիլու, եւ այնու կերպիւ գնացին ի տուն Ճէնէրալին։ Այլ արդ ճէնէրալն ընդ տեսանելն զնա ի վերուստ այնու հայոց Պարոնաց զգեստովն, սկսաւ աղաղակել հայոց բարբառովն. Այ դու Բարոն, բարի ես գոլման գոլդ ի բարին, եկ, եկ ի վեր։ Իսկ Թովմաճանն զահի հարեալ հարցանէ բաթերային թէ աստ հայք գտանին, եւ թէ այն հայերէն խօսողն ո՞վ իցէ։ Եւ նա ասեր թէ ճէնէրալն է։ Իսկ Թովմաճանն ոշ հաւատայր եւ յորժամ ներկայացան առաջի ճէնէրալին, ճէնէրալն ելեալ գիրկս էարկ զպարանոցաւն Թովմաճանին եւ ասէ, նիստ եւ հանգիստ լեր, զի ես ի Մատրաս եւ ի Պանկալայ Մեծամեծ Պարոնաց գրագրութիւն արարի եւ զլեզու հայերէնն ուսայ, եւ զայս վիճակ իշխանութեանս եւս ձերազգին Պարոնաց միջնորդութեամբն ընկալայ. Վասն որոյ ես այժմ պարտական եմ ծառայութիւն առնել բոլոր հայոց ազգին։ ուստի այժմ զինչ ինչ պիտոյ իցէ քեզ ասա համարձակ, եւ ես ծառայեցից քեզ. ես տեսանեմ որ եւ կարծեմ թէ փոքր ինչ նաչաղութիւն էլ ունիս այժմ կոչեցից զբժիշկս. եւ կաց աստէն զաւուրս ինչ եւ զքեզ մեր նաւաւ առաքեցից հանգստեամբ։

Եւ Թովմաճանն զգեցեալ էր զպատուական Մատրասի պարոնացն զգեստն, եւ զգտակն նոցին մանիլու, եւ այնու կերպիւ գնացին ի տուն Ճէնէրալին։ Այլ արդ ճէնէրալն ընդ տեսանելն զնա ի վերուստ այնու հայոց Պարոնաց զգեստովն, սկսաւ աղաղակել հայոց բարբառովն. Այ դու Բարոն, բարի ես գոլման գոլդ ի բարին, եկ, եկ ի վեր։ Իսկ Թովմաճանն զահի հարեալ հարցանէ բաթերային թէ աստ հայք գտանին, եւ թէ այն հայերէն խօսողն ո՞վ իցէ։ Եւ նա ասեր թէ ճէնէրալն է։ Իսկ Թովմաճանն ոշ հաւատայր եւ յորժամ ներկայացան առաջի ճէնէրալին, ճէնէրալն ելեալ գիրկս էարկ զպարանոցաւն Թովմաճանին եւ ասէ, նիստ եւ հանգիստ լեր, զի ես ի Մատրաս եւ ի Պանկալայ Մեծամեծ Պարոնաց գրագրութիւն արարի եւ զլեզու հայերէնն ուսայ, եւ զայս վիճակ իշխանութեանս եւս ձերազգին Պարոնաց միջնորդութեամբն ընկալայ. Վասն որոյ ես այժմ պարտական եմ ծառայութիւն առնել բոլոր հայոց ազգին։ ուստի այժմ զինչ ինչ պիտոյ իցէ քեզ ասա համարձակ, եւ ես ծառայեցից քեզ. ես տեսանեմ որ եւ կարծեմ թէ փոքր ինչ նաչաղութիւն էլ ունիս այժմ կոչեցից զբժիշկս. եւ կաց աստէն զաւուրս ինչ եւ զքեզ մեր նաւաւ առաքեցից հանգստեամբ։

“And Tovmachanian, dressed in the clothes worn by the great Armenian merchants of Madras and donning one of their Manila caps or hats as well, went to the general’s residence [in the company of a Catholic padre].

“And Tovmachanian, dressed in the clothes worn by the great Armenian merchants of Madras and donning one of their Manila caps or hats as well, went to the general’s residence [in the company of a Catholic padre].

Now, upon seeing him from above wearing the dress of Armenian merchants, the General began to exclaim and gesticulate loudly in the Armenian dialect [of Julfa]: “Greetings to you sir, welcome, welcome. Please come upstairs.” And Tovmachanian, struck with astonishment asked the padre if there were any Armenians [on the island] and who that person speaking Armenian was. And the Padre responded, saying that it was the General. Tovmachanian did not believe him at first, and when they approached the General, the General gave embraced him around his neck and told him: “Have a seat and be calm, for I worked as a scribe for Armenian merchants in Bengal and Madras and learned the Armenian language there. I also owe my appointment to this position to the mediation of those gentlemen belonging to your nation, on account of which I am indebted to serving all those who belong to the Armenian nation. Therefore, do not hesitate to tell me what you need and I shall serve you. I see and I think that you have an illness of sorts, and I will now call a physician [to examine you]. Stay here for some days and we will send you off in comfort with one of our ships.” (Vark‘ ew patmut‘iwn Tovmachanean Mahtesi Tēr Hovhannisi Konstandnupōlsets‘woy oroy ěnd eresun těrut‘iwns shrjeal vacharakanut‘eamb ew husk hetoy verstin darts‘arareal i bnik k‘aghak‘ iwr kostandnupōlis dse  ̇rnadri and k‘ahanay hIgnatios yepiskoposē yotanasnerort ami hasaki iwroy apa ekeal dadarē i vans rabunapeti metsi Mkhitaray abbay hōr i Venetik [The life and history of Mahtesi Ter Hovhannes Tovmachanian of Constantinople, who, after wondering through thirty states conducting commerce, once again returns to his native city of Constantinople where he is anointed a celibate priest by Bishop Ignatius at the age of seventy and then comes to repose at the monastery of the great master, Abbot Mkhitar, in Venice]. MS 1688, folio 273. The French governor-general of the island during Tovmachanian’s brief visit was Jean Daniel Dumas. I thank my friend Merujan Karapetyan for bringing this passage to my attention many years ago and for several discussions on this episode since then. Merujan is in the process of publishing this valuable travel manuscript.)

̇rnadri and k‘ahanay hIgnatios yepiskoposē yotanasnerort ami hasaki iwroy apa ekeal dadarē i vans rabunapeti metsi Mkhitaray abbay hōr i Venetik [The life and history of Mahtesi Ter Hovhannes Tovmachanian of Constantinople, who, after wondering through thirty states conducting commerce, once again returns to his native city of Constantinople where he is anointed a celibate priest by Bishop Ignatius at the age of seventy and then comes to repose at the monastery of the great master, Abbot Mkhitar, in Venice]. MS 1688, folio 273. The French governor-general of the island during Tovmachanian’s brief visit was Jean Daniel Dumas. I thank my friend Merujan Karapetyan for bringing this passage to my attention many years ago and for several discussions on this episode since then. Merujan is in the process of publishing this valuable travel manuscript.)

The French governor-general’s ability to identify Tovmachanian from a distance as belonging to the Armenian “nation” based exclusively on his clothing and specifically on account of his “manila hat” invokes the intimate relationship between clothing and social identity on which sociologists from Thorstein Veblen and Georg Simell to Pierre Bourdieu have long speculated. Clothing, or how individuals choose to cover their bodies, is a crucial way of fashioning identities whether in terms of class, gender, race, or, as in the case of Tovmachanian, perceived membership to a “trade diaspora” community. “Clothes make the man” as the saying goes. To dress in a particular way is to make a statement about oneself and also about the group to which one belongs. Clothing establishes distinction and draws out the individual or collectivity from a larger mass of people. It is a marker of social and individual identity; a system of codes through which individuals communicate signals to others about their place in the larger world.

In the early modern period, communities of merchants in the highly cosmopolitan world of long-distance trade often resorted to wearing distinctive garb to help set themselves apart from others. Collective self-fashioning became all the more imperative in bustling centers of early modern long-distance commerce where members of diverse ethno-religious communities commingled in the bazars and market places of Mediterranean and Indian Ocean port cities teeming with multitudes from virtually every corner of the globe. Among the different “nations” or trade diasporas whose distinctive sartorial practices were readily noted by observers were Armenian merchants from the suburb of Julfa who had established a far-flung network of trade settlements stretching from London in the West to Canton and Manila in the East. In India, Armenian merchants, though small in number, were virtually ubiquitous. They stood out from other mercantile communities not only because they were very successful in trade, but also because they wore distinct clothing. A British soldier in Calcutta in the early decades of the nineteenth century, Lieutenant R. G. Wallace, is one of few observers to note the unusual sartorial practices used by Armenian merchants in India to distinguish themselves from others. For Wallace, the Armenians he came across were a “highly respectable body of wealthy subjects.” In his work, Fifteen Years in India, the lieutenant characterizes Armenians in India as follows:

In the early modern period, communities of merchants in the highly cosmopolitan world of long-distance trade often resorted to wearing distinctive garb to help set themselves apart from others. Collective self-fashioning became all the more imperative in bustling centers of early modern long-distance commerce where members of diverse ethno-religious communities commingled in the bazars and market places of Mediterranean and Indian Ocean port cities teeming with multitudes from virtually every corner of the globe. Among the different “nations” or trade diasporas whose distinctive sartorial practices were readily noted by observers were Armenian merchants from the suburb of Julfa who had established a far-flung network of trade settlements stretching from London in the West to Canton and Manila in the East. In India, Armenian merchants, though small in number, were virtually ubiquitous. They stood out from other mercantile communities not only because they were very successful in trade, but also because they wore distinct clothing. A British soldier in Calcutta in the early decades of the nineteenth century, Lieutenant R. G. Wallace, is one of few observers to note the unusual sartorial practices used by Armenian merchants in India to distinguish themselves from others. For Wallace, the Armenians he came across were a “highly respectable body of wealthy subjects.” In his work, Fifteen Years in India, the lieutenant characterizes Armenians in India as follows:

“Their complexion is fair, and in address they are pleasing, but the Armenian costume gives them a remarkable appearance. It is, however, very becoming. The cap is of black velvet, and triangularly shaped, the frock is generally of the same materials, but embraces the neck closely, flowing down to the knee, something like a surtout. Many of them, however, both in Calcutta and Bombay, may be said to emulate the Bondstreet gentry, having assumed the English dress in all things except the cap, which is retained as a mark of national distinction.”

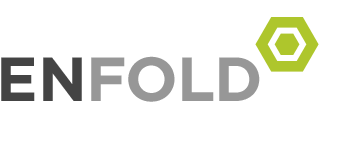

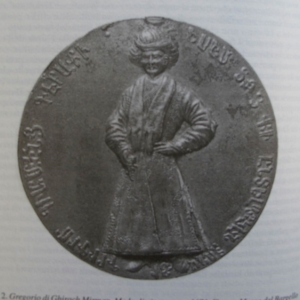

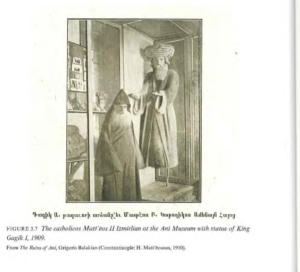

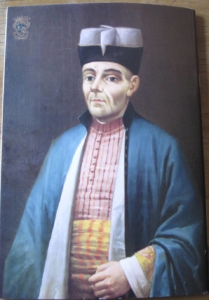

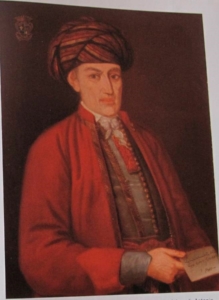

That as long-time residents in British India, many Armenians residing in the presidency towns of Bombay, Calcutta, and Madras would gradually adopt English and European customs and “emulate the Bondstreet gentry” in fashion should not come as much of a surprise. What is most noteworthy in Wallace’s remarkable observations above is the tenacity with which Armenians there clung on to their funny-looking velvet caps or hats, even while they dressed as European gentlemen. Wallace notes this and perspicaciously concludes that the retention of the hat had to do with its place as a “mark of national distinction.” Indeed, the triangular hat seems to have been donned by Armenian merchants originally from the suburb of Julfa no matter where they were residing. Julfan merchants both in Calcutta, Madras, or Amsterdam and Venice are first represented in portraits and sketches as wearing these unusual caps with a series of triangulated peaks towering above their heads only in the eighteenth century. Earlier representations of Armenian merchants from Julfa appear to indicate that sartorially speaking little separated them from their fellow Muslim merchants in the Indian Ocean or West Asia. For instance, like other Armenian merchants from the Ottoman Empire, or Muslim Iranians or South Asians, Julfans in the seventeenth century appear to have worn Islamicate garb including the striking looking turbans. By the eighteenth century, however, the exquisite turbans seem to have given way to the “triangularly shaped” hat among most Julfans. Next to nothing is known about these hats. When they first became fashionable and what their provenance was remains a complete mystery, as literary sources regarding this matter are silent. What we have as sources are painted portraits from the period, especially watercolor sketches of Armenians in India, as well as a number of similar sketches from Venice, and some oil painting portraits from Amsterdam. All these sources represent Armenians sporting the same triangular hats upon the sight of which one was expected immediately to distinguish their wearers as Armenian merchants.

That as long-time residents in British India, many Armenians residing in the presidency towns of Bombay, Calcutta, and Madras would gradually adopt English and European customs and “emulate the Bondstreet gentry” in fashion should not come as much of a surprise. What is most noteworthy in Wallace’s remarkable observations above is the tenacity with which Armenians there clung on to their funny-looking velvet caps or hats, even while they dressed as European gentlemen. Wallace notes this and perspicaciously concludes that the retention of the hat had to do with its place as a “mark of national distinction.” Indeed, the triangular hat seems to have been donned by Armenian merchants originally from the suburb of Julfa no matter where they were residing. Julfan merchants both in Calcutta, Madras, or Amsterdam and Venice are first represented in portraits and sketches as wearing these unusual caps with a series of triangulated peaks towering above their heads only in the eighteenth century. Earlier representations of Armenian merchants from Julfa appear to indicate that sartorially speaking little separated them from their fellow Muslim merchants in the Indian Ocean or West Asia. For instance, like other Armenian merchants from the Ottoman Empire, or Muslim Iranians or South Asians, Julfans in the seventeenth century appear to have worn Islamicate garb including the striking looking turbans. By the eighteenth century, however, the exquisite turbans seem to have given way to the “triangularly shaped” hat among most Julfans. Next to nothing is known about these hats. When they first became fashionable and what their provenance was remains a complete mystery, as literary sources regarding this matter are silent. What we have as sources are painted portraits from the period, especially watercolor sketches of Armenians in India, as well as a number of similar sketches from Venice, and some oil painting portraits from Amsterdam. All these sources represent Armenians sporting the same triangular hats upon the sight of which one was expected immediately to distinguish their wearers as Armenian merchants.