A Persianate Epistolary Adab?

A Persianate Epistolary Adab?

December 21, 2018

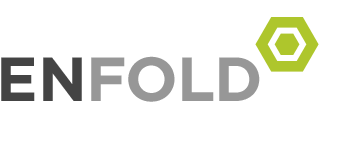

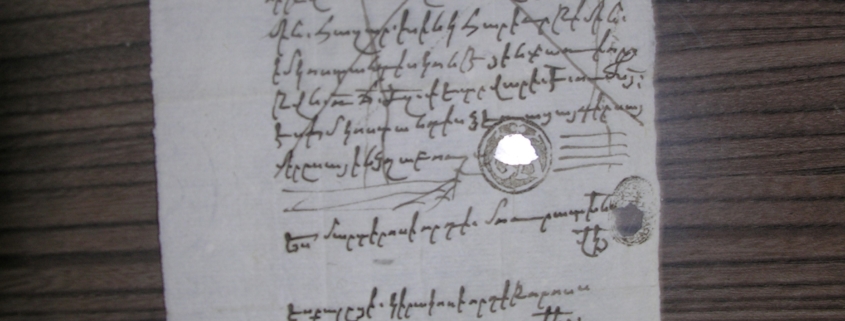

One cold winter evening in New Julfa, Isfahan, I was puzzled by a commercial document I had photographed earlier. It was many moons ago in mid-February of 2005, and I was a graduate student, lodging at the All Savior’s Cathedral in New Julfa. That morning like many others during my stay there I had been photographing seventeenth century commercial documents drawn up in the now-extinct dialect of mercantile Armenian known as Julfa dialect and stored at the archive inside the cathedral. One of the folders (Զանազան Նիւթերով գրութիւններ 1643-1699 Առեւտրական գրութիւններ վարդապետների կնիքներով Zanazan Niwt‘erov Grut‘iwnnner, Nor Jugha, 1643-1699 [Documents Concerning Various Matters, New Julfa, 1643-1699 Commercial documents with seals of Vardapets, folder 5]), contained several papers that had their seals removed in a methodical manner so as not to damage the document’s text. I was puzzled and confused, and as almost always when stumped by a Julfan document, I resorted to Edmund Herzig’s unpublished dissertation for help. Herzig noted that removing seals was a Persian custom of invalidating legal documents. His source was the work of the French Huguenot traveler and jeweler Chevalier Jean Chardin (1643-1713) who had lived in Safavid Iran for a number of years, knew the Armenians well, and had acquired a good command of the Persian language. Chardin’s travels were published in 1811 in a ten-volume edition by P. Langlès, Voyages du Chevalier Chardin en Perse, et autres Lieux de l’Orient.

They contain to date the most authoritative account of the manners and customs of people in Iran and are indispensable for anyone working on Julfa. On page 171 of volume four, Chardin adroitly explains the puzzle that had confounded me in my room inside the All Savior’s Cathedral thirteen years ago. Here is his account of why and how Iranians went to great lengths to remove seals from their documents after the latter had outlived their purpose.

They contain to date the most authoritative account of the manners and customs of people in Iran and are indispensable for anyone working on Julfa. On page 171 of volume four, Chardin adroitly explains the puzzle that had confounded me in my room inside the All Savior’s Cathedral thirteen years ago. Here is his account of why and how Iranians went to great lengths to remove seals from their documents after the latter had outlived their purpose.

“I have observed elsewhere, that the Persians do not at all tear up paper when they withdraw their bills and other acts. They remove the seal with a penknife [canif] and then they wet it in water and make out of it a small ball which they shove into a hole where it vanishes and turns into powder.*

Langlès’s footnote clarifies this further: *All the Muslims, regardless of being Sunni or Shi’ia, allow themselves to be scrupulous of destroying and above all casting among garbage a piece of useless paper, because, they say, it is possible that someone might have written or may write on it the name of God.

[J’ai observé dans un autre endroit , que les Persans ne déchirent point le papier, lorsqu’ils retirent leurs billets ou autres actes. Ils en ôtent le sceau avec le canif, puis le mouillent en l’eau, et en font un petit peloton, qu’ils fourrent en un trou, où il se dissipe, et s’en va en poudre.*

* Tout les Musulmans, indistincetement, sunnytes ou chy’ites, se font in grand scruple de détruire, et sur tout de jeter parmi les ordures, un morceau de papier inutile, parce que disent-ils. il est possibe qu’on y ait inscrit, ou inscrive le nom de Dieu.]

This bizarre practice reminds one of one reason why medieval Maghrebi Jews had an aversion to destroying documents in a cavalier manner and instead deposited their papers in a special chamber attached to a Synagogue and known as a geniza for ritual “burial” at a later period. The underlying logic in both cases was injunction against accidentally defiling the name of God.

Chardin’s observations above and the Julfan documentation that has survived (see images above) demonstrate that Christian Armenians in Julfa and across their global diaspora were essentially Persianate in their manners. They breathed in the same cultural air as their Iranian and other Muslim counterparts and operated with the same “adab” or code of conduct for proper behavior whether in their ethical relations with others or in their commercial dealings. Even the way they carried their seals hanging from their necks with a silk thread or on their rings made of agate stone was practically identical, as Chardin also suggests in other volumes of his travelogue. This “adab of epistolarity and commerce” is perhaps nowhere better demonstrated than in the way Julfans sealed (or unsealed) documents, the way they wrote up their letters, or even glued together long pieces of paper to form scrolls on which they kept their accounts known as Tomars (տոմար).

Here then are the three documents in the Julfa archive with which I began this post. The first item in my exhibit (see image below) is from the year 1662 and is a “commenda” partnership that is crossed out.

Dated 1111 in the greater Armenian calendar and the Azaria year of Nakha 26, or July 14, 1662, the document is between Constantil (Constantine?) son of Ramaz (Rhamazan) Կոստանդիլս ռամազի որդի and Simon son of Ptum պտումի որդի պարոն Սիմոն. Even though the contract is crossed out, the drawers of this paper felt the need to remove its four seals.

Dated 1111 in the greater Armenian calendar and the Azaria year of Nakha 26, or July 14, 1662, the document is between Constantil (Constantine?) son of Ramaz (Rhamazan) Կոստանդիլս ռամազի որդի and Simon son of Ptum պտումի որդի պարոն Սիմոն. Even though the contract is crossed out, the drawers of this paper felt the need to remove its four seals.

The second item in exhibit (see image below) below is a promissory note between Constant son of Ramaz ռամազի որդի Կոստանդս and Herampet [sic]  son of Hakob հակոբի որդի հէրամպետի for a whopping sum of 4,000 tomans. This appears to be the same man who five years earlier had misspelled his own name. Here he gets his own name correct but butchers the name of the other party to the contract. Once again the seals are cut out.

son of Hakob հակոբի որդի հէրամպետի for a whopping sum of 4,000 tomans. This appears to be the same man who five years earlier had misspelled his own name. Here he gets his own name correct but butchers the name of the other party to the contract. Once again the seals are cut out.

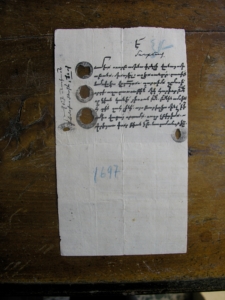

Finally, lest we think that seal cutting was only confined to Constantil son of Ramaz(an), we have another promissory note drawn up by the head priests of the All Savior’s Cathedral where I stayed in 2005. The signatories are Mikael, Alexander, David, and Moses Vardapets (միքայէլ աղէքսանդր դաւիթ եւ մովսէս վարդապէտքս) stating that they owe Davud son of Shemas (շըմասի որդի աղա դաւութ) a more modest sum of one hundred tomans. Again the seals have been carefully removed with a penknife in the manner that Chardin describes as being the common practice in Iran among Persianate people. What is odd about  this last document, is that of the four archimandrites who wrote up this document, only three appear to have affixed (and then gouged out) their seals on the left margin which was the space on Julfan documents where only priests and the reigning Kalandar (governor or mayor of Julfa) were expected to apply seals. The Kalandar at the time was Ghukas son of Khoja Petros [Խօջայ պետրոսի որդի ղուկազս վկայեմ], who served at this post first in 1687 and then from 1692-1703, if Vazken Ghougasian appendix at the end of his useful book is to be trusted. The bottom of the document or the space where merchants applied seals has presumably the seal of the creditor, a certain Dawood son of Shemas, who was most likely the same person who is identified as one of the official dragomans or translators (“linguist”) of the East India Company in Iran. This Dawood’s papers are stored in the Archivio di Stato of Firenze and a few are in the India Office Records at the British Library. We cannot be certain that this is indeed the same Davut Shemasian because one downside of cutting out seals is that while it preserves the document for posterity and for historians like me, it also obliterates the sealer’s identity.

this last document, is that of the four archimandrites who wrote up this document, only three appear to have affixed (and then gouged out) their seals on the left margin which was the space on Julfan documents where only priests and the reigning Kalandar (governor or mayor of Julfa) were expected to apply seals. The Kalandar at the time was Ghukas son of Khoja Petros [Խօջայ պետրոսի որդի ղուկազս վկայեմ], who served at this post first in 1687 and then from 1692-1703, if Vazken Ghougasian appendix at the end of his useful book is to be trusted. The bottom of the document or the space where merchants applied seals has presumably the seal of the creditor, a certain Dawood son of Shemas, who was most likely the same person who is identified as one of the official dragomans or translators (“linguist”) of the East India Company in Iran. This Dawood’s papers are stored in the Archivio di Stato of Firenze and a few are in the India Office Records at the British Library. We cannot be certain that this is indeed the same Davut Shemasian because one downside of cutting out seals is that while it preserves the document for posterity and for historians like me, it also obliterates the sealer’s identity.