What’s in a Merchant’s Head?

November 2, 2015

We know much about the commodities Armenian and other merchants in India handled but nearly nothing on what they read and therefore what they may have thought in the silent lair of their skulls. In this connection, merchant libraries from the East India Company’s probate records of inventories of estates are an ideal source for figuring out the mental horizons and thoughts that merchants might have carried in their heads. A quick analysis of one such private library, that of the Julfan merchant Owen John Petruse, of Calcutta is quite revealing. I thank Liz Chater for first bringing the existence of this inventory to my attention as well as for sharing with me her transcription of its contents.

At the time of his death in Calcutta in 1797, Mr. Owen John Petruse owned over a hundred titles in his private library.* A good many of these were dictionaries, mostly for English and Armenian but a few for Persian, such as Francis Gladwin’s “A compendious vocabulary English and Persian: including all the oriental” (1780) and a grammar manual for “Portugueze” and English. Milton’s works, and especially “Paradise Lost,” are mentioned as are several works in the genre of what we would describe today as self-help, such as Hester Chapone’s (Mulso) (1727–1801) very popular “Letters on the Improvement of the Mind Addressed to a Young Lady” (1773), three volumes of a certain “Ladys Encyclopaedia” and one of “A Young Gentleman and Ladys Monitor,” as well as “two Musick books,” three of “The Pleasing Instructor or Entertaining Moralist Consisting of Select Essays, Relations, Visions and Allegories,” presumably for the edification of Mr. Petruse’s daughters or wife. Interestingly, for a man who spent most of his time engaged in commerce, there are only two items that address this topic, namely, “The Universal Dictionary of Trade Commerce” and John Mair’s “Bookkeeping Methodized.” Tomes on law, most notably Sir Edward Coke’s four-volume “The Institutes of the Lawes of England” (n.d.) the standard work in common law, and three or four other titles on common law entitled “attorneys practice at bench” and “Attorneys Complete Pocket Book,” take up the place of commerce or accounting. The preponderance of this merchant’s books cover the subjects of grammar, dictionaries, and law already mentioned as well as geography and history, including an unspecified one covering “The History of England,” another on the “War in America” followed by a work on charters on the British colonies in America, and thirteen unnamed books simply referred to as “American books,” including a two-volume “American Dictionary.” The latter might be a scribal error for Armenian Dictionary, in which case the reference would be to Abbot Mkhitar’s famous two-volume Dictionary of the Armenian Language (1749 and 1769), which sold fairly well in India in the two decades before Mr. Petruse passed away. Works of Armenian history include an enigmatic “history of Constantine the Great,” and the equally enigmatic

At the time of his death in Calcutta in 1797, Mr. Owen John Petruse owned over a hundred titles in his private library.* A good many of these were dictionaries, mostly for English and Armenian but a few for Persian, such as Francis Gladwin’s “A compendious vocabulary English and Persian: including all the oriental” (1780) and a grammar manual for “Portugueze” and English. Milton’s works, and especially “Paradise Lost,” are mentioned as are several works in the genre of what we would describe today as self-help, such as Hester Chapone’s (Mulso) (1727–1801) very popular “Letters on the Improvement of the Mind Addressed to a Young Lady” (1773), three volumes of a certain “Ladys Encyclopaedia” and one of “A Young Gentleman and Ladys Monitor,” as well as “two Musick books,” three of “The Pleasing Instructor or Entertaining Moralist Consisting of Select Essays, Relations, Visions and Allegories,” presumably for the edification of Mr. Petruse’s daughters or wife. Interestingly, for a man who spent most of his time engaged in commerce, there are only two items that address this topic, namely, “The Universal Dictionary of Trade Commerce” and John Mair’s “Bookkeeping Methodized.” Tomes on law, most notably Sir Edward Coke’s four-volume “The Institutes of the Lawes of England” (n.d.) the standard work in common law, and three or four other titles on common law entitled “attorneys practice at bench” and “Attorneys Complete Pocket Book,” take up the place of commerce or accounting. The preponderance of this merchant’s books cover the subjects of grammar, dictionaries, and law already mentioned as well as geography and history, including an unspecified one covering “The History of England,” another on the “War in America” followed by a work on charters on the British colonies in America, and thirteen unnamed books simply referred to as “American books,” including a two-volume “American Dictionary.” The latter might be a scribal error for Armenian Dictionary, in which case the reference would be to Abbot Mkhitar’s famous two-volume Dictionary of the Armenian Language (1749 and 1769), which sold fairly well in India in the two decades before Mr. Petruse passed away. Works of Armenian history include an enigmatic “history of Constantine the Great,” and the equally enigmatic  “Mesrope elegant orations,” as well as Moses Khorenatsi’s (Chorenses) famous “History of the Armenians,” first printed in Amsterdam in 1695, reissued in Venice in 1752, and reprinted in London with a Latin translation (1736) that served Gibbon as an important source, and finally in Venice in 1752. What is perhaps most noteworthy about this merchant’s inventory of books is the presence of works with distinctly Roman themes. For instance, our merchant owned several volumes of Gibbon’s [Gibsons] famous account of Roman history as well as two volumes of Montesquieu’s “Spirit of the Laws.” The presence of works on Roman history in this merchant’s library appears to confirm a larger interest in Roman history and republican virtue evident during the second half of the eighteenth century among Armenians in India, as the case of Eduard Raphael Gharamiants demonstrates.** The fact that Mr. Petruse owned Montesquieu’s “Spirit of the Laws” indicates that the republican and Enlightenment ideas in the constitutional work of the “Madras group” were more than likely influenced by this work. This is the first evidence I have come across that Montesquieu’s work was available in India in the late eighteenth century. In addition, Petruse owned over seven different dictionaries and grammar manuals, mostly for English but also for Persian and Portuguese, and one would assume for Armenian as well, though none is mentioned as such. The estate papers of Matheus di Joannes of Canton (d. 1794) suggest that the books in his voluminous private library were remarkable similar in content, genre, and theme to Petruse’s library.*** Further work on inventories of other Armenian merchants from India is needed before we can draw larger conclusions on what type of books merchants typically read and owned in their collections and therefore what ideas likely animated their minds.**** That the print editions and places of publication for Armenian books are largely absent in some of these inventories is unfortunate because it prevents us from knowing how many of the Armenian-language books owned by merchants in the Indian Ocean world were actually published in Venice as opposed to Amsterdam, for instance.

“Mesrope elegant orations,” as well as Moses Khorenatsi’s (Chorenses) famous “History of the Armenians,” first printed in Amsterdam in 1695, reissued in Venice in 1752, and reprinted in London with a Latin translation (1736) that served Gibbon as an important source, and finally in Venice in 1752. What is perhaps most noteworthy about this merchant’s inventory of books is the presence of works with distinctly Roman themes. For instance, our merchant owned several volumes of Gibbon’s [Gibsons] famous account of Roman history as well as two volumes of Montesquieu’s “Spirit of the Laws.” The presence of works on Roman history in this merchant’s library appears to confirm a larger interest in Roman history and republican virtue evident during the second half of the eighteenth century among Armenians in India, as the case of Eduard Raphael Gharamiants demonstrates.** The fact that Mr. Petruse owned Montesquieu’s “Spirit of the Laws” indicates that the republican and Enlightenment ideas in the constitutional work of the “Madras group” were more than likely influenced by this work. This is the first evidence I have come across that Montesquieu’s work was available in India in the late eighteenth century. In addition, Petruse owned over seven different dictionaries and grammar manuals, mostly for English but also for Persian and Portuguese, and one would assume for Armenian as well, though none is mentioned as such. The estate papers of Matheus di Joannes of Canton (d. 1794) suggest that the books in his voluminous private library were remarkable similar in content, genre, and theme to Petruse’s library.*** Further work on inventories of other Armenian merchants from India is needed before we can draw larger conclusions on what type of books merchants typically read and owned in their collections and therefore what ideas likely animated their minds.**** That the print editions and places of publication for Armenian books are largely absent in some of these inventories is unfortunate because it prevents us from knowing how many of the Armenian-language books owned by merchants in the Indian Ocean world were actually published in Venice as opposed to Amsterdam, for instance.

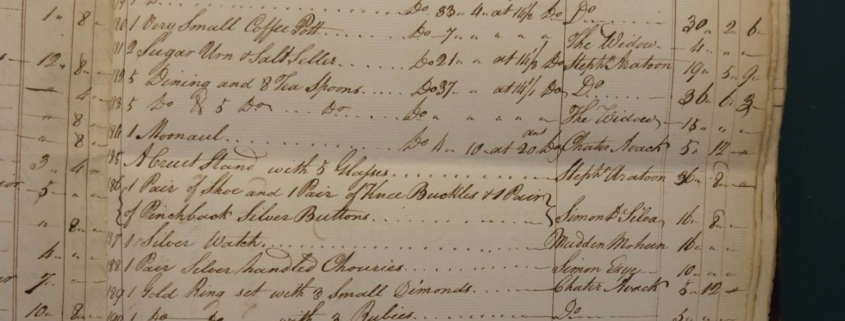

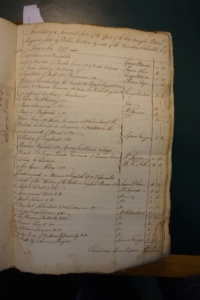

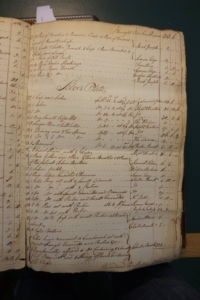

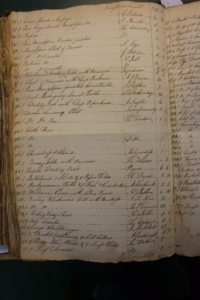

* “Inventory & Account Sales of the Effects of the Late Owenjohn Petruse, deceased, Sold by Public Auction by order of the Executrix, Calcutta 7 November 1797,” in Bengal Inventories, British Library, IOR, L/AG/34/27/20, Inventory Numbers 81 and 82.

* “Inventory & Account Sales of the Effects of the Late Owenjohn Petruse, deceased, Sold by Public Auction by order of the Executrix, Calcutta 7 November 1797,” in Bengal Inventories, British Library, IOR, L/AG/34/27/20, Inventory Numbers 81 and 82.

** The latter, as is well known, commissioned an Armenian translation of Charles Rollin’s “Histoire romaine depuis la fondation de Rome jusqu’à la bataille d’Actium…” (Paris 1738-1748) as a precondition for the endowment he bequeathed the Mkhitarist Congregation, patronage money that was later used for the opening of Collegio Armeno Moorat Raphael in Venice. For an analysis, see “La fioritura culturale delle comunità armene in India e nel mondo dell’Oceano indiano e lo sviluppo del pensiero sociale e politico durante il secolo XVIII” [The Cultural Flourishing of the Armenian Communities in India and the Indian Ocean World and the Development of their Social and Political Thought during the Eighteenth Century] in Armenia: Impronte di una civiltà eds. Levon B. Zekiyan, Gabriela Uluhogian, and Vartan Karapetian (Venice, 2011), 207-211.

***See the partial listing of this merchant’s library in Carl T. Smith, “An Eighteenth-Century Macao Armenian Merchant Prince.” Revista de Cultura 6 (2003): 120–129

****For a provisional start in this direction, see Sebouh David Aslanian, “A Reader Responds to Joseph Emin’s Life and Adventures: Notes towards a History of Reading in Late Eighteenth Century Madras,” Handes Amsorya (Vienna/Yerevan, 2012), 9-64