Of Signets and Seals

December 29, 2018

Shared epistolary practices between Julfan Armenians and other Iranians included the “material conditions of letter writing”1 recently explored in James Daybell’s fine study of early modern English letter writing conventions. For Julfan writers as for their counterparts in Iran as well as the subjects studied by Daybell on the extreme edge of Eurasia, writing letters or preparing legal documents was no simple task of merely picking up “pen and paper.” Rather, it was a laborious and complex undertaking. As Daybell discusses in connection to English writers of epistles, “various skills had to be acquired and materials assembled before sitting down to write a letter.” (30)

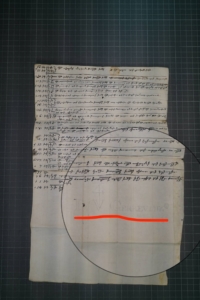

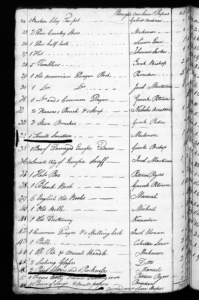

The repertoire of materials and tools required for this task was imaginably quite diverse. This included access to paper (some Julfan trading firms like the Coja Minasians purchased large quantities of fine writing paper from Europe and particularly from the famed Dutch paper manufacturer L.V. Gerrevink in Amsterdam–see watermark of “L.V. Gerrevink” in image below); pens and penknives (Julfans probably used “pens made of reeds brought from the southern parts of Persia” as the English traveler Jonas Hanway describes in this travelogue in reference to Iranians in general), perhaps even some varieties of feathers for the fashioning of quills; a writing desk referred by the Julfans as ըսքրիթոր or “escritor” (see image 3 where “1 small escritore (item 24), paper cutters and penknife and 5 quirs [sic] of small and large papers are listed in an inventory of estate of Martin Massey who passed away in Calcutta in 21 April 1798, source British Library); an ink pot and accompanying dust or sand box to hold pumice with which to dry or “blot” wet ink; wax, floss, ribbons, seals or signets used for sealing folded paper and creating the “envelope effect” before the invention of the gummed envelope in the 1840s. Most importantly perhaps for our purposes here, nearly every writer needed his or her unique seal մուհր or մօր (P. muhr, muhur, A seal, seal-ring) for authenticating documents and signaling drawer’s identity to the reader(s) as well as validating a piece of legally enforceable paper.(My provisional repertoire of writing implements above is drawn from Daybell, 30 and from inventories of estates belonging to Armenian merchants in Calcutta and Madras and stored in the India Office Records in London).

It is here with the use of the authenticating seal that I think one can also see the influence of the Persianate world on the Julfan Armenians. Since I have spent the greater part of the last fifteen years scrutinizing literally thousands of merchants’ and priests’ seals on the paper cargo traveling on the Santa Catharina, I have developed a fascination (some might say obsession) with this topic. Again, Jean Chardin is a most useful guide here as to how seals were carried and used by merchants and government officials in Safavid Iran. Here is the erudite Huguenot discussing the use of seals in vol 5, 454-455:

“Everyone knows, in my opinion, that the Orientals do not have the practice of making valid deeds by signature, as we have in the West; this is neither practiced nor even known to them. They put their seal in the place where we place our name. And we must not think that it is easy to steal their seal, for they wear it hung around the neck by a silk cord between the shirt and the dress, never leaving it except in the bath. Nor should it be easy to counterfeit it; for, on the contrary, it is very certain that it happens much more rarely among them than it happens among us to counterfeit the signature. Other people wear their seal on their finger, like a ring. These seals are ordinarily made from agate stone or carnelian, are oval or square, and the size of a denier [coin] on which is [engraved] their name or some sentence of the Koran….”

Chacun sait, à mon avis, que les Orientaux n’ont point la pratique de rendre les actes valides par des signature, comme on l’a en Occident; cela n’est ni pratiqué, niu même connu chez eux. Ils apposent leur sceau, ou cachet, au lieu que nous mettons notre nom; et il ne faut pas penser qu’il soit aisé de prendre leur sceau, car ils le portent pendu au cou par un cordon de soie entre la chemisette et la robe, ne le quittant jamais que dans le bain. On ne doit pas penser non plus qu’il soit aisé de le contrefaire; car, au contraire, il est fort sûr que cela arrive beaucoup plus rarement chez eux, qu’il n’arrive parmi nous de contrefaire la signature. D’autres gens portent leur sceu au doigt, en façon de bague. Ces sceaux sont ordinarement des agates ou conalines ovales ou carrées, de la grandeur d’un denier, sur lesquelles est leur nom ou quelque sentence de l’Alcoran. (454-455)

This information is corroborated by the English traveler Jonas Hanway in “An Historical Account of the British Trade over the Caspian Sea” in 1753 (vol. 1 317) and again by Carsten Niebuhr in his “Description de l’Arabie: faite sur les observations propres et des avis recueillis dans les lieux mêmes.” (90)

That Julfans and Iranians shared a Persianate habitus of carrying their seals in the form of signet rings made of agate stone is evident in the inventory of of the estate of Martin Massey whose probate papers in Calcutta have already been mentioned. In his detailed inventory compiled in Calcutta, we read that the deceased owned a “silver Ring with a Seal” (see image 6). Julfans probably carried their seals around their necks more often than on their fingers is also clearly demonstrated in a legal brief on the trial of the Santa Catharina written by Philip Carteret Webb in the 1750s.

“The Armenians set the Impression of their Seal, or Chop, in Ink, to all Instruments they Sign; and, in their less Solemn Papers, such as Bills of Exchange, &c. they rarely subscribe their Names, but put the Impression of their Chop, which they constantly wear, fastened to a Chain, round their Necks.” (Webb, 24)

1. James Daybell, The Material Letter in Early Modern England: Manuscript Letters and the Culture and Practices of Letter-Writing, 1512-1635 (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2012), 43