Of Letter Cutting and Fonts: Print culture and the Circulation of technology Across the Indian Ocean

May 31, 2019

“…it must be remembered that punch cutting, striking and casting moulds were all long and delicate operations which only specialised craftsmen could perform. A punch cutter, for instance, needed to be a very experienced man with years of practice behind him. At the beginning of printing, an industry created out of nothing, the earliest printers had to cut their own punches, make their own matrices, and cast their own type: each of which tasks would have taken up a great deal of time and money, and probably had to be carried out with the help of only the most rudimentary equipment. If they met with any success it was only because so many of them had formerly been goldsmiths….The designing and cutting of type took up a great deal of time… Furthermore, the production of new type cost a lot of money and when the chance came printers would buy material which came on to the market after a death or a bankruptcy. This happened only rarely.” (Lucien Febvre and Henri-Jean Martin, The Coming of the Book, 58-59)

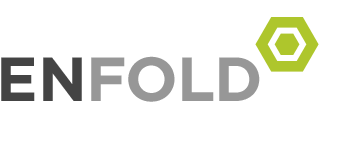

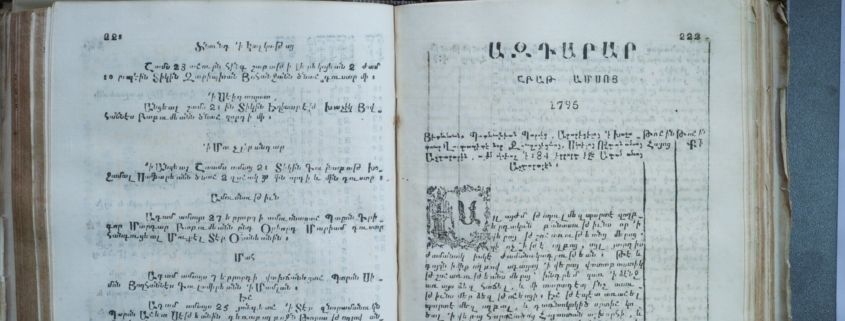

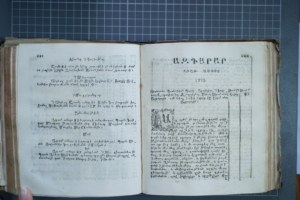

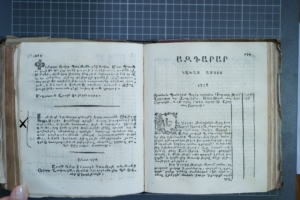

One of the greatest obstacles hindering the spread of print technology to the world beyond the confines of early modern Europe and America was the absence of the letter-cutters and mold makers. This was especially the case when the types that needed to be designed and cut were for non-Latin script printing. Armenian printers faced this hurdle from early on, and often if not nearly always, the only way to overcome it for them was to send their priest/printers to Europe where they could find professional letter cutters and commission them, at great expense, to create unique punches, molds, and matrices, through which the work of printing could finally get underway. This was the case of Hovannes Jughayets‘i (c. 1610-1660) who acquired a German letter cutter in Rome and traveled with him to Livorno to have the letter types in Armenian prepared away from the watchful eyes of Rome’s censors. Matteos Tsarets‘i faced the same obstacle and had to travel to Amsterdam in 1656 to contract Christoffel Van Dyke, a letter cutter associated with the famed Elsevier firm of printers in order to have elegant Armenian types designed and cut. In Julfa in 1636, the first Armenian printer there Khachatur Kesarats‘i)(1590-1646) could not acquire Armenian types from Europe, though not for want of trying through his contacts with Isfahan’s Carmelite missionaries. He had no choice but to have types designed and cut locally with results that were unsatisfactory (the types were made of wood instead of metal), thus compelling him to send his pupil Hovannes Jughayets‘i (mentioned above) to Europe to have new types cast. Building the actual “platen” press in situ was difficult enough, but cutting letter type represented a difficulty of a different magnitude. Apart from sending a trusted representative to Europe to commission the making of new Armenian type, one alternative available to Armenian printers in Asia was to acquire used Armenian type on the open market. This usually became possible when a printer who owned his own types (including the steel punches, copper matrices, led fonts, and accompanying implements) went bankrupt and had his equipment repossessed by the court which then auctioned off his goods. In 1728, for instance, Abbot Mkhit‘ar of Venice managed to purchase the Armenian types that had been designed by the Hungarian letter cutter Nicholas Misztótfalusi Kis (1650-1702) and used the Vanandets‘i press in Amsterdam from 1685 until its bankruptcy in 1717. According to correspondence between Mkhit‘ar and his Armenian merchant-contact in the Dutch capital who purchased the letter types for the Mkhitarists and shipped them to San Lazzaro, the fonts had been confiscated by the court and were available for purchase to the highest bidder. We are not always privileged enough to possess a paper trail on how letter types and matrices on the open market moved or circulated from one location to another across the Armenian diaspora. The case of the last Armenian press in India in the early modern period, namely the Holy Nazareth Church press set up in Calcutta in 1796 by Hovsep Kahana Stepannosean, is exceptional in this regard. In its short-lived history between 1796 and 1798, the press published a total of five books, including two that were editio princeps (first editions of manuscript works). (Hakob Irazek, Patmut‘iwn Hndkahay Tbagrut‘ean [History of Indo-Armenian Printing], Antelias, 1986, 158) The History of Catholicos Abraham of Crete, which chronicled the history of the Armenian Church under Nadir Shah’s tumultuous first years, is one such example.

in the Dutch capital who purchased the letter types for the Mkhitarists and shipped them to San Lazzaro, the fonts had been confiscated by the court and were available for purchase to the highest bidder. We are not always privileged enough to possess a paper trail on how letter types and matrices on the open market moved or circulated from one location to another across the Armenian diaspora. The case of the last Armenian press in India in the early modern period, namely the Holy Nazareth Church press set up in Calcutta in 1796 by Hovsep Kahana Stepannosean, is exceptional in this regard. In its short-lived history between 1796 and 1798, the press published a total of five books, including two that were editio princeps (first editions of manuscript works). (Hakob Irazek, Patmut‘iwn Hndkahay Tbagrut‘ean [History of Indo-Armenian Printing], Antelias, 1986, 158) The History of Catholicos Abraham of Crete, which chronicled the history of the Armenian Church under Nadir Shah’s tumultuous first years, is one such example.

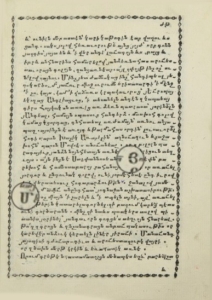

The latter work has a section titled “Concerning the Progress of this our new printing press, how it was founded and what it followed in its entirety”1 where the publisher provides the following interesting account of how this press got its start: “One day, some time ago, a certain young man unexpectedly came across in a market or at a fair with stalls owned by Englishmen who had come from Europe, impounded Armenian letter types equipped with all the requisite implements. Upon seeing them ready at hand and being aware that he would be esteemed by those who shared his intent, this young man, that is, the noble and valiant Mister Moses the son of the deceased Mister Khachik Arakel, immediately and without delay purchased them. He then presented them [as a gift] to the senior priest of this place, Ter Hovsep‘ Stepannosean himself, the modest priest.”2 (See accomopanying images) Regretfully, this fleeting account does not name the English merchant or how and when he had brought to Calcutta used Armenian punches, matrices, and types. It also does not tell us who had cut these types in the first place. Fortunately, a year prior to the publication of The History and the opening of the Holy Nazareth Press, the first Armenian periodical Azdarar, published in Madras, offered the following suggestive account in its monthly notices and announcements to its readers:

“We hear that in Bengal they have purchased the printing press of England, where they printed the Book of Moses Khorenats‘i along with its translation, and plan to establish it [there, in Calcutta] to print whatever books they can. On account of this, not only ought we be proud, but we should also encourage such people, that is those who because they occasion good acts, enrich our nation. And if this news is reliable, we unconditionally assure the public to expect to see the fruits of this [endeavor] in a short time.”3 (See images)

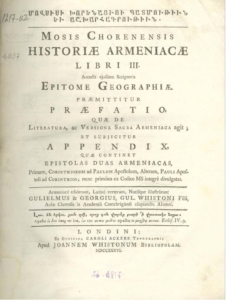

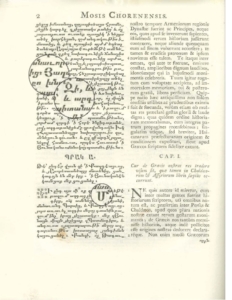

The reference here is, of course, to the celebrated publication in London in 1736 of Gulielmus & Georgius Whistoni’s Mosis Chorenensis Historiae Armeniacae. (See image 5) This first translation of Movses Khorenats‘i’s classic History of the Armenians in the British capital used Armenian types that were designed and cut by the English punch cutter William Caslon (1693-1766). Given the spotty documentation on these letter types, we can only infer that the types were repossessed by the court and subsequently purchased by an enterprising English merchant and transported and sold in a kind if flea market in Calcutta. A careful examination of the letter types of the Whiston brothers’ iconic edition of 1736 and the types used in Calcutta indicate that they are indeed one and the same (See image 6 and 7)

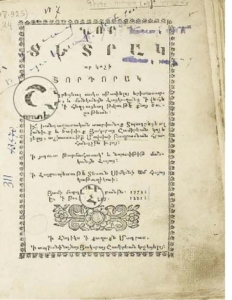

Less straightforward is the path taken by the fonts that made possible Madras’s (and India’s) first Armenian printing press, established also inside the compound of an Armenian church. The brainchild of Madras’s wealthiest Armenian merchant and one of the city’s business tycoons, Shahamir Sultanum Shahamirean and his twenty-seven-year-old son Hakop, the press was set up in the family compound that also became the site for Madras’s Saint Mary’s Armenian church in 1771 or early 1772. Until recently, next to nothing was known on how the father and son team in Madras had managed to circumvent the problem of acquiring Armenian types in Madras. The publication of John Lane’s The Diaspora of Armenian Printing in 2012 shed unexpected light on the matter. According to Lane, who provides no sources or evidence for his claim, the Shahamireans “must have acquired their type from Venice, for it matches the rather crude and old-fashioned bolorgir used by Paolo Moneta at Rome in 1674 and Michelangelo Barboni in Venice in the 1680s.” (164) Indeed, even a cursory examination of the two fonts demonstrates the validity of Lane’s claim, at least as far as their remarkable resemblance in concerned. (See images 8 and 9) Either a precise measurement and scrutiny of the types’ size and idiosyncrasies or more documentation is needed before concluding that Shahamirean did indeed have Barboni’s hundred-year-old types purchased and shipped to Madras. The only direct evidence (not seen by Lane) appears to be limited to information in the epistolary exchange between Armenian Catholic priests from the Mkhitarist Congregation in Venice then visiting Madras and their Abbot back home in San Lazzaro. In his letter to Abbot Melkonian, dated 20 October 1770, Sukias Aghamalean, one of the monks visiting Madras relates how Shahamir Shahamirean had approached him with a request for Armenian types that he and his son could use for their newly built printing press at their home.

“He asks for a favor from your eminence, that is that we send him a few letter types for the printing of some letters pertaining to his commerce with those [of our nation] in Europe. His son being a bit of an inventor, had built a printing press in their home. And having spent great expenses, they had letters engraved in cooper one by one, entirely uneven and crooked. When he begged us for this favor, we told him of the difficulties involved, including, first, of the recent royal [sic] decree of Venice prohibiting the taking of letter types outside of Venice. However, if it is possible, let us send [him] some of the letter types from the Holy Scriptures, as many as would fill two folios of the Gospels, along with all the implements, that is the cases, punctuation marks, and so on, so that they may have those of our nation in Europe bring them over here.”4

Ambiguous as it is, the evidence above suggests at least two possibilities. First, it would appear that Hakob Shahamirean (the son) had a platen wooden press built in Madras and had also initially commissioned a local goldsmith to cut or engrave, in copper, “entirely uneven and crooked” Armenian letter types. Given the stylistic resemblance of the Shahamirean letter types to those of Barboni, it could be that the local goldsmith used the Barboni exemplars as a model. More probable, however, is the second suggestion implicit in this letter, namely that Shahamirean was unsatisfied with the initial letter types and had one of his Armenian contacts in Venice purchase Barboni’s used type and ship them to Madras.

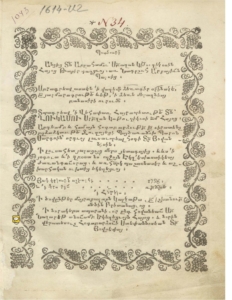

Caption: Title page of T‘ught‘ Siroy ew Miabanut‘ean [Letter of Love and Concord], Venice, printing press of Michelangelo Barboni,1683

Caption: Title Page of Shahamir Shahamirean’s Nor Tetrak or Kochi Hordorak, Madras, 1772

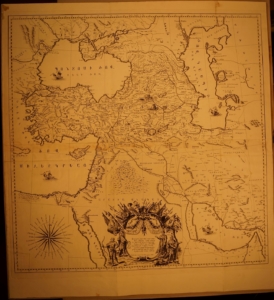

More than likely, this contact would have been Shahamirian’s long-time business associate and go-between in Venice, Paron Arak‘el Abelean, a merchant of unknown origins and history. The same Arak‘el was Shahamirean’s go-between and the person who arranged on his friend’s behalf to commission an unknown local Venetian printer to design, engrave and print Shahamirean’s masterpiece “Atlas of Greater Armenia” (Ashkharhatsoyts‘ Hayastaneayts‘) in 1778 (see images 10 and 11), a significant milestone in Armenian cartographic printing that until recently had been mistakenly attributed to the Mkhit‘arist Order but since Sahak Djemjemian’s short work, Kartisagrut‘ean Dprots‘ Mĕ Surb Ghazari Mēj (19-22) has been considered a work of unknown provenance whose printing in Venice and shipment to India was certainly arranged by the Venice-based Armenian merchant-associate of Shahamirean, Paron Arak‘el Abelean.5

Caption: Shahamirean map of Greater Armenia, Venice 1778

Caption: Inset of Shahamirean map of Greater Armenia, Venice 1778

Given this link between Shahamirean and Abelean, it would not be farfetched to conjecture that the same Abelean had found, five or six years earlier in 1771 or 1772, Boldoni’s old letter types on sale in Venice and promptly shipped them to his friend in Madras.

Notes:

1.“Յաղագս յառաջանալոյն սոյն այս մերս նորոգ տպար[ա]նին. Եթէ զի արդ հիմ եւ յորոց հետեւի ‘գլխովին:’”

2.“Մինչյետ ժամնակաց ինչ հանդիպեալ յեղակարծում` յաւուր միոջ ուրումն երիտասարդի ի մէնջ ի շուկայս, կամ ի վաճառս կրպակաւորաց` յեւրոպայ եկողաց Անգլիացւոց, ի տեսանելն անդէն զկապտեայ գիրս Հայկական տառից առ ձեռն պատրաստ` յօրինե[ա]լն յԱնգեալ, համայն սպասուք հանդերձ. մտախոհ գոլով կամաց կցորդաց, գնհատեալ առժամայն` առնու անյապաղ. այսինքն է առոյգ եւ թարմահաս որդին` լուսաւորե[ա]լ հոգի պարոն Խաչիկ Առաքելին` ազնուազուն եւ քաջախոհն` պարոն Մովսէս անուանեալ: որ զբոլորն պարագայիւք յանձն նոյնհետայն առնէ աւագ երիցուն տեղւոյս. այն ինքն է Ստեփաննոսեան Տ[է]ր Յովսէփին` բարեխոհ եւ համեստաբարոյ քահանայն:”

3. “Լսեմք զի ՚ի բանկալայ գնեալ են Հայոց տպարանն Անգլիոյ որ զՄովսէս Խորենացի գիրքն` եւ որոյ թարգմանութեամբն տպեալ են, եւ կամին հաստատել զայն եւ տպագրել զկարելի գրեանս, որոյ վասն ոչ թէ միայն ուրախ լինիլ պարտէ` այլ եւ քաջալերել այնպիսեաց, այսինքն` նոցայ որք պատճառ այդպիսի բարեգործութեան լինելով հարստացուցանեն զազգս մեր, եւ եթէ հաւաստի իցէ զլուրն աներկբայապէս յուսադրեմք հասարակութեան ակնկալնուլ տեսանել զպտուղ բանին միջոց սակաւ ժամանակի:”

4. “Սա խնդիր ինչ խնդրէ ի գերյարգութենէդ, այսինքն զի առաքեսջիք սակաւ ինչ տառս կապարեայս ի տպագրութիւն թղֆթոց ինչ վերաբերելոց տուրեւառութեան իւրեանց՝ զօրէն ազգացն եւրոպիոյ։ Որդի սորայ փոքր մի հնարագէտ գոլով արարեալ էր գործատուն տպագրութեան ի տան իւրեանց, եւ բազում ծախս արարեալ՝ տուեալ էին փորագրել զտառս մի մի ի վերայ պղնձոյ, ամենեւին անկարթ եւ անհաւասար։ Ի խնդրել նորա զայս, փոքր մի դժուարին ցուցակ զառաջինն՝ զվճիռն թագաւորութեան Վենետկոյ պատճառեալ վասն ոչ տանելոյ այլուր զտառս։ Սակայն եթէ հնար է, առաքեսջիք ի տարից Աստուածաշնչից որչափ բաւական լինի լցուցանել երկու երեսս թղթոյ կտակարանին, հանդերձ ամենայն հանգամանօք, այսինքն կտրոցիւք, կիւտիւք, եւն., զի եւ ազգն Եւրոպիոյ Վասն այսպիսի թղթոց տան բերել յԵւրոպիոյ.”

5. The 1962 essay by the late Vladimir [i.e., Vardan] Grigoryan, “Shahamir Shahamiryani ‘Askharhatsoyts‘ Hayastaneayts‘’ ĕ,” Banber Matenadarani, 6 (1962): 353-362 (355) claims the work as a specimen of Mkhitarist cartography. Djemjemian, on the basis of correspondence in the archives of San Lazzaro, demonstrates that Abelean had communicated with the monks asking for help but had not found the assistance he needed there. I thank Merujan Karapetyan for reminding me of Djemjemian’s brief monograph and alerting me to the role of Arak‘el Abelean in procuring the map in question.